Whats interesting about Inuit art is that it is not necessarily a traditional art form.

Not many Inuit artefacts exist pre 1700, apart from ritual objects used by shamans etc. These objects were usually kept quite small in consideration of the Inuit's nomadic lifestyle.

By the middle of the 1800s, most of the art created by the Inuit was aimed at a 'tourist' market, and objects were made to be traded and sold.

Inuit art as we know it today came into existence in 1948-49 largely due to James Houston (more detail below). He encouraged the Inuit to use their talents in creating art objects to help solve their economic problems. In this regard they were assisted by the Inuit Co-operatives .

Despite Inuit art not being a traditional art form dating back centuries etc, I think it still gives a glimpse into the way of life of these communities and how they view their world and how they want their stories to be told?

Its great to see the work made by these Inuit artists being used across Canada on stamps etc as a celebration of the Inuit contribution to the heritage of Canada, I think that is how folklore and storytelling should be celebrated.

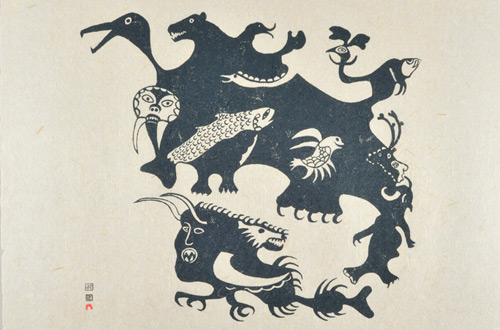

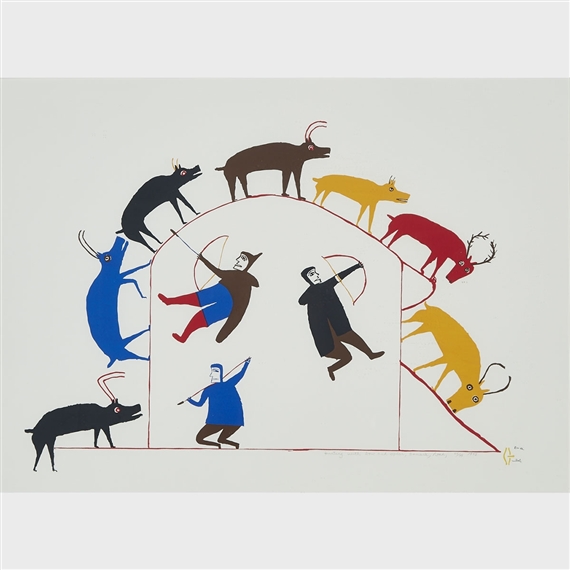

Aesthetically, I love the flat, block shapes and mischievous type personas the animals depicted have with their exaggerated aspects - they're really charming and playful.

I definitely want to get into printmaking next week to make work about my stories in print - inspired by these beautiful Inuit block prints and Carson Ellis' Illimat cards.

Printmaking

(https://www.historymuseum.ca/capedorsetprints/history/1950s.php)

Before 1957, graphic art on paper was rare in the Canadian Eastern Arctic, although individuals such as Noogooshoweetok and Peter Pitseolak created occasional drawings and watercolours when materials were available. Despite the lack of paper, a strong Inuit graphic tradition has existed for many centuries. Incised designs on ivory, stone and musk ox horn — decorative patterns on tools and amulets that evoke the spiritual and animal world —reach back over a thousand years. Appliquéd designs on hide garments and bags sewn by Inuit women evidence an equally vibrant graphic tradition in sealskin and caribou-skin sewing. These traditions continue today using modern and traditional materials.

Peter Pitseolak

Printmaking was introduced in Cape Dorset in late 1957 by James Houston (1921–2005), an artist, writer and the Area Administrator for South Baffin Island. He was employed by the federal government to encourage the production of carving and crafts in the North and to promote Inuit art in the South. In Cape Dorset’s newly erected crafts shop, Houston along with Osuitok Ipeelee (1922–2005) and Kananginak Pootoogook (1935-2010) began to experiment with fabric and paper printing using linoleum floor tiles cut with simple designs.

Wanting to bring greater knowledge of printing to the Arctic, James Houston studied printmaking in Japan from November 1958 until February 1959 with the master woodcut printmaker Un’ichi Hiratsuka (1895–1997). Houston returned to Cape Dorset and shared what he had learned in Japan with the Inuit printmakers. Adapting and inventing, the Cape Dorset artists developed their own unique ways of making direct stencil and stonecut relief prints. The Inuit printmakers created their first official catalogued collection of prints in 1959, numbering 41 works in total. These artworks were released to the public with great fanfare in February 1960 at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Meanwhile, to better manage their fledgling studio enterprise, the Cape Dorset artists incorporated a co-operative association called the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, which continues to operate today.

Prints from the 60s:

Kenojuak Ashevak, 1960

Kenojuak Ashevak, 1960

Simeonie Kopapik, 1963

From the 80s

Lucy Qinnuayuak, 1982

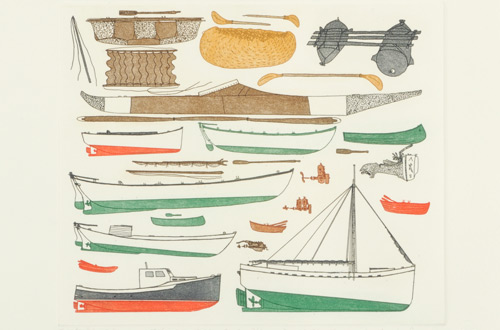

Kananginak Pootoogook, 1981-82

Prints by Pauta Saila, Inuit artist (1916 - 2009):

he was also a stone sculptor and was well known for his 'dancing bears'

and some prints by his wife Pitaloosie Saila

This print 'Arctic Madonna' was used by UNICEF as a greetings card in 1983.

and this one "Fishermans Dream" was used by Canada Post in 1977.

Its great that Canada have recognised the contribution of Inuit art to the wider cultural art heritage of Canada.

Similar to the Czech stamps I have, I think folklore is something that should celebrated through accessible means like stamps and everyday objects. Rather than just the blooming Queens head.

Tapestry

http://arcticcultureforum.org/blog1/?page_id=637

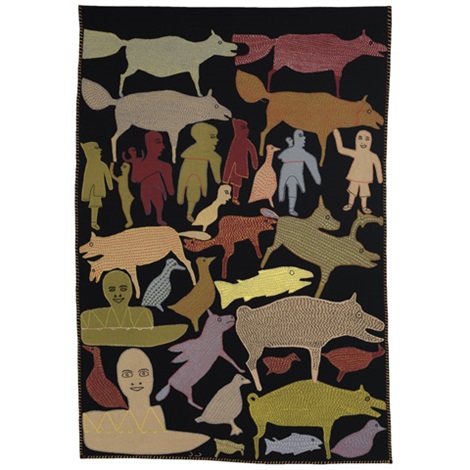

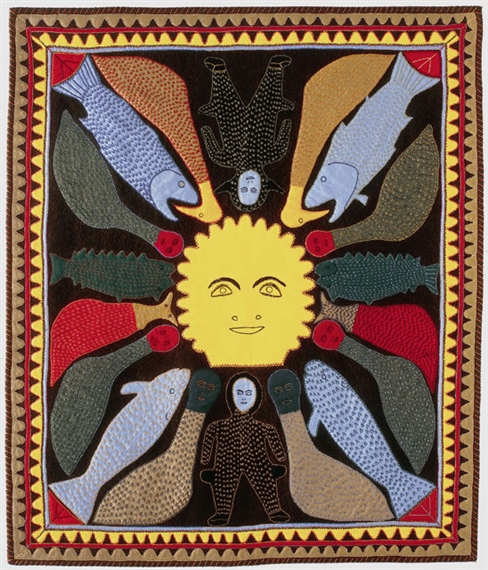

With no written tradition, the Inuit used tapestries such as these to convey their history and beliefs. Inuit women scraped and chewed caribou and seal skins to soften them in the course of creating clothes, using sinew for thread. The application of women’s traditional sewing skills to the production of textile art first started in the settlement of Baker Lake, Nunavut, in the 1960s. After making wool duffle mittens, socks, and clothing, seamstresses used the leftover multi-coloured pieces of fabric to make art to hang on walls. In embracing a foreign artistic medium, the women of Baker Lake made their wall hangings a vehicle for expressing centuries-old Inuit traditions, and gave birth to a uniquely Canadian art form.

Traditionally, sewing was a vital survival skill for Inuit living on the land. The women’s ingenuity and skillful stitching transformed animal hides into clothing, blankets, tents, and even into seafaring vessels such as the kayak. The entire family depended upon the sewing ability of women, from the men on the hunt to babies cuddled in their mother’s parka hood. In the long winter months in their igloos, as women decorated their parkas and garments with lavish colorful decorations, their daughters would learn to sew by observation. All these age-old skills have been transferred to the modern textile art of today’s Inuit women

Jessie Oonark

(1906-1985)

Canadian Inuit artist of the Utkuhihalingmiut Utkuhiksalingmiut whose wall hangings, prints and drawings are in major collections including the National Gallery of Canada.

Her work portrays the nomadic lifestyle she led for 5 decades. She was 54 years old when her work was first published – she was a very active and prolific artist over the next 19 years, creating a body of work that won considerable critical acclaim and made her one of Canada's best known Inuit artists.

Utkuhiksalingmiut oral history and legends were strongly reflected in Jessie's artwork.

The Utkukhalingmiut had many taboos, one of which was the drawing of images. According to Marie Bouchard— a researcher, art historian, and community worker who lived in Baker Lake for many years— "Oonark's grandmother repeatedly warned her that images could come to life in the dark of night."

Marion Tu'luuq

(1910-2002)

Marion was an Inuk artist of mixed media & textiles.

In the 1960s, she was part of a semi-nomadic group of Inuit who, facing the threat of starvation, were forced to change their nomadic lifestyle and move to the settlement of Baker Lake. While she was relieved to escape hardship, she expressed sorrow at the loss of her nomadic lifestyle. Her personal history emerges in her work as she attends to the significance of land and family in contemporary Inuit life.

Tuu'luq used embroidery thread, felt, and dense woollen fabrics. She was a part of a circle of northern fabric artists (including Jessie Oonark and Irene Avaalaaqiaq Tiktaalaaq) who helped establish the contemporary art form of large-scale, two-dimensional, embroidered textile works.

No comments:

Post a Comment